April 29, 2021

On April 30, 1975, the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese Army, effectively ending the Vietnam War. In the days before, U.S. forces evacuated thousands of Americans and South Vietnamese. American diplomats were on the frontlines, organizing what would be the most ambitious helicopter evacuation in history.

The logistics of issuing visas and evacuating these Vietnamese and American citizens were not glamorous but were essential. American diplomats were behind every detail. Some diplomats showed exceptional bravery saving Vietnamese citizens who would have faced persecution under the new regime.

These artifacts and photos in our collection offer a glimpse of what diplomats and refugees experienced during the Fall of Saigon. More broadly, they show the challenging and dangerous circumstances diplomats may encounter while performing their work.

Saigon in April 1975

Although the United States had withdrawn its military forces from Vietnam after the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973, approximately 5,000 Americans remained–including diplomats still working in the U.S. embassy in Saigon. While President Nixon threatened a forceful response to a violation of the treaty, many factors, including lack of domestic support and the distraction of the Watergate scandal, provided an opportunity for the NVA to launch an offensive.

Throughout March and April 1975, the North Vietnamese Army captured more and more Southern cities. South Vietnamese citizens began to flee in mass numbers. The fall of the second-largest city, Da Nang, sparked even more refugees to depart.

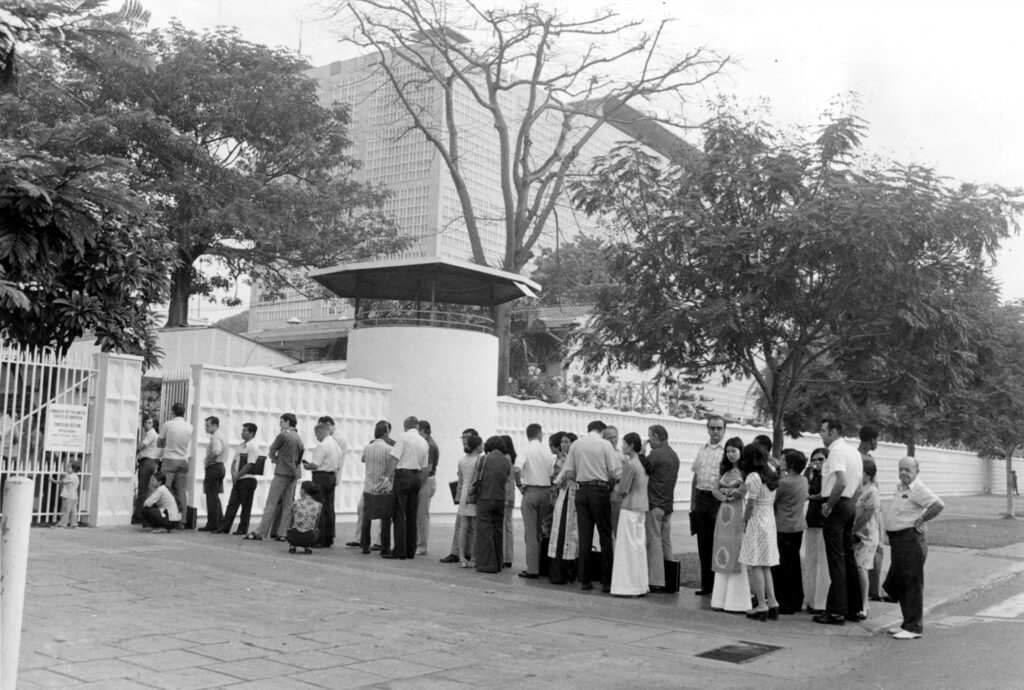

In Saigon, South Vietnamese lined up at the embassy to gain entry to the United States. Patti Morton, a trailblazing Diplomatic Security Special Agent serving as a Regional Security Officer in Saigon—the first woman in such a role—documented the scene on the embassy grounds in the footage below, taken on an unknown day in April.

The Final Days: The Fall of Saigon

On April 29, 1975, North Vietnamese troops shelled Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut Air Base. U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin then ordered the evacuation of Saigon. As a signal to Americans in Saigon that the evacuation had begun, Armed Forces Radio started to play “White Christmas” on repeat.

By this point, sea lanes were blocked and planes could not land in Saigon, leaving only one option for an evacuation: a helicopter airlift.

After the defense attaché compound was attacked, the U.S. embassy became the sole departure point for helicopters. The original plans called to only evacuate Americans, but Ambassador Martin insisted on evacuating South Vietnamese government officials and the embassy’s local staff.

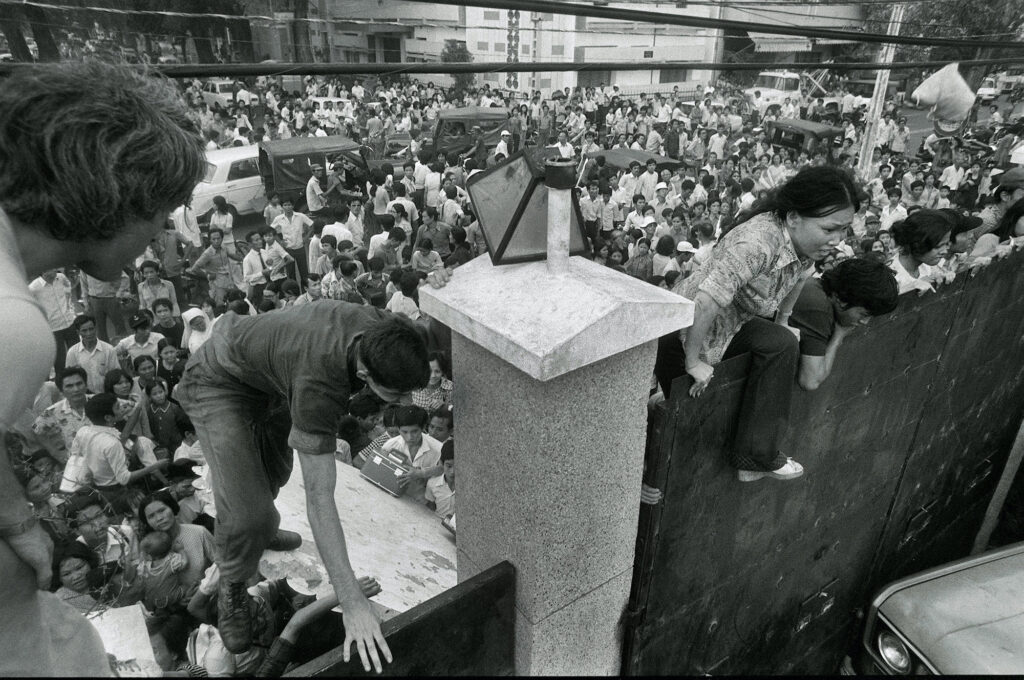

Meanwhile, 10,000 South Vietnamese waited at the embassy gates, hoping to make it onto a helicopter.

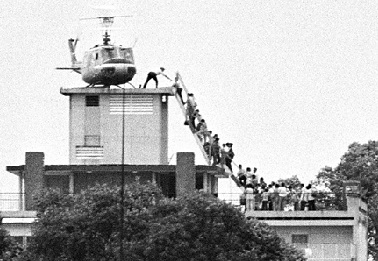

From April 29th to April 30th, helicopters landed at 10-minute intervals in the embassy, including landing on the embassy roof. With some pilots flying for 19 hours straight, over 7,000 people were evacuated, including 5,500 Vietnamese, in less than 24 hours.

Diplomat Wolfgang J. Lehmann and the Final Hour at the Embassy

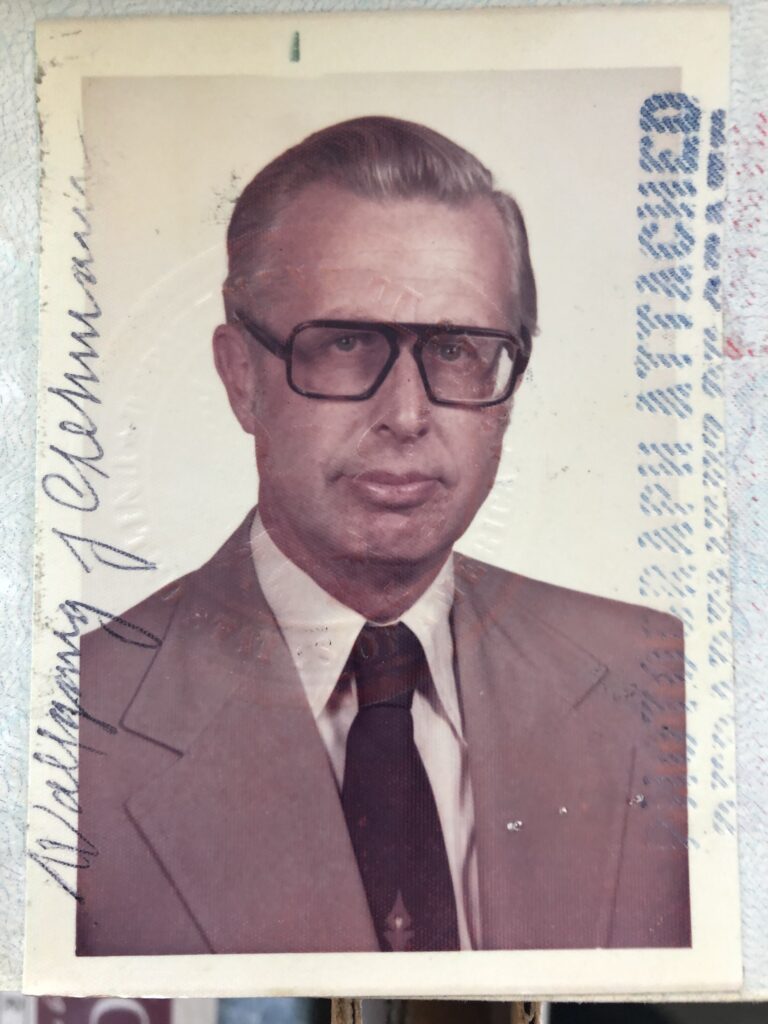

One diplomat working to facilitate the evacuation was Wolfgang J. Lehmann, who served as the Deputy Chief of Mission at the U.S. embassy in Saigon. Lehmann was one of the last people to leave the embassy on April 30th.

After witnessing Ambassador Martin depart on a helicopter and then departing on the next one along with about six other embassy staff members, Lehmann recalled the flight to a waiting evacuation ship:

“We could see the lights of the North Vietnamese convoys approaching the city…The chopper was packed with the rest of the staff and remaining civilian guards…and it was utterly silent except for the rotors of the engine. I don’t think I said a word on the way out and I don’t think anybody else did. The prevailing emotion was tremendous sadness.”

– Wolfgang J. Lehmann

This day planner was used by Wolfgang Lehmann, the Deputy Chief of Mission in Saigon. The planner was donated to the museum in 2019 by Wolfgang’s nephew, Walter Lehmann.

On the page documenting the day of April 30, 1975, you can see that Lehmann made two notes: “05:20 left Saigon” and “06:10 arrived USS Denver.”

FROM THE COLLECTION

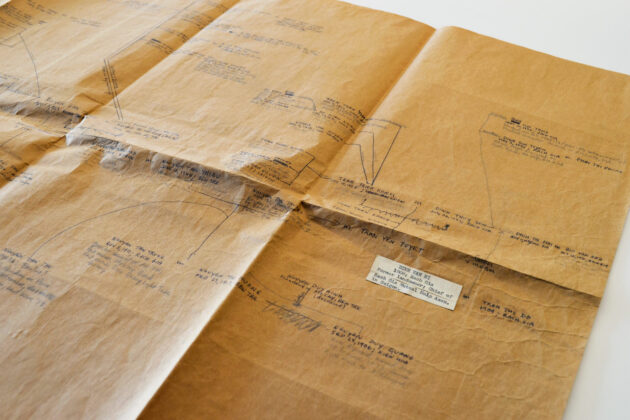

South Vietnam Political Relationships Chart

President Ford Thanks Diplomats for Historic Evacuation

Lehmann kept and framed a copy of this personal message sent on May 5, 1975 from President Ford to Ambassador Graham Martin, thanking him and the entire embassy staff for the successful evacuation effort. The telegram reads:

“Dear Graham: I want to express my deep appreciation to you and your entire staff for the successful evacuation of Americans and Vietnamese from Saigon. The tireless dedication of your mission and its skillful performance under the most severe pressure was vital to the accomplishment of this most difficult and delicate operation. Please accept as well my sincere personal compliments. Your courage and steadiness at this critical period enabled us to evacuate our own citizens and a very large number of endangered Vietnamese. I hope you will convey to your entire staff my deep gratitude and that of the American people for a job well done. Sincerely, Gerald R. Ford”

Diplomat Evacuates Hundreds of Vietnamese Refugees in Cần Thơ

While Saigon was falling, the rest of South Vietnam was also evacuating as quickly as possible. Approximately 100 miles away In Cần Thơ, one diplomat saved hundreds of Vietnamese refugees by devising and leading a risky evacuation.

Francis Terry McNamara served as Consul General in Cần Thơ, Vietnam at the time of the U.S. evacuation. In the hectic days prior to the final pull-out, McNamara’s orders from the U.S. Embassy were to evacuate only the Americans; they were only going to provide helicopters with enough room to evacuate the 18 or so American employees — for expediency and security reasons.

McNamara knew that he could not leave his loyal Vietnamese employees or their families behind, as they would likely face detention or even death for working for the Americans.

McNamara refused to evacuate just the Americans from the consulate, as were the instructions from the evacuation coordinator in Saigon. Saigon desperately needed Cần Thơ’s helicopters, the coordinator relayed.

Using his negotiation skills, McNamara said they could have the consulate’s helicopters now, rather than in six hours after evacuating Americans, if McNamara could evacuate everyone, including Vietnamese staff, by boat.

After they got disconnected, McNamara was able to get Jacobsen back on the phone. He recalls,

“Reluctantly, he agreed, “You’ve got your permission to go by water,” he granted. “Just get the hell out of there.” I had finally worn him down. The whole world was ending around him, and he could not get me off the telephone.”

– Consul General Francis Terry McNamara

Utilizing his skills as a former sailor, McNamara commandeered some barges with help from a USAID colleague and quickly loaded the remaining Americans, Vietnamese employees, and their families for evacuation.

McNamara captained the convoy down a Mekong Delta tributary, which was stopped at one point by the South Vietnamese Navy and took fire from Viet Cong troops. The U.S. Navy was supposed to meet them at the mouth of the South China Sea, but a ship never arrived.

The barge bobbed in the open sea for a few hours until they saw some lights. It was an American freighter contracted by the CIA for evacuations. However, they had no idea who McNamara and his band of about 300 Vietnamese and Americans were. They were finally convinced to take everyone on board to safety.

In 2019, Ambassador McNamara donated the U.S. flag and the Consular flags, taken from the consulate building as they evacuated and then subsequently flown on the barge he commanded during the evacuation. Over the years, the blues of the flags have turned to deep red due to a chemical reaction that occurs in some older plastic-based materials, including fabrics.

FROM THE COLLECTION

U.S. Consular Flag

The Bravery and Resilience of Vietnamese Refugees

No one showed more bravery in this evacuation than the Vietnamese that went to extreme risks to evacuate their families from the war zone, risking their lives to board helicopters as quickly as possible. Some of those refugees would go on to become American citizens and serve their country, including serving as diplomats. One such story is that of Anne D. Pham, now a U.S. Foreign Service officer who was evacuated from Vietnam as a small child.

“…Brave individuals like USAID officers Joseph Gettier and Mel Chatman sought alternative, last-ditch means to rescue people. They commandeered military transport barges that had been used to carry supplies during the war…That was how my parents left their homeland with their six young children. Our escape down the Saigon River, with darkness setting in, was a dangerous one. Near Vung Tau Harbor, where the river opens to the Pacific Ocean, we came under rocket fire. Thankfully, as I was only 3 years old, I have only faint memories of the journey. As the barge drifted out to sea, crammed with refugees, my father held me close and solemnly said to my eldest brother: “Take a good look at your country. It will be the last time you see it.” The next day, we were plucked out of the ocean from our barge and boarded the U.S.S. Sgt. Andrew Miller.”

Pham would later join the Foreign Service and become a faculty member of the National Defense University. She had opportunities to meet and honor “her heroes” that played a part in the evacuation. She recounts:

“By saving me on that fateful day, they planted the seeds of strength and hope that helped me to achieve my dream of working for the State Department…While I am a product of a painful chapter in history, I am also a product of the greatness of America, with its diverse society, democratic ideals and opportunity for all. Only in America can a former refugee child become a senior adviser working for the same agency as do the Foreign Service officers who saved her.”

– Foreign Service Officer Anne D. Pham

References:

Tears Before the Rain: An Oral History of the Fall of South Vietnam

No comments:

Post a Comment